Latecomers to the car market decided to build their own supply chains from scratch. Because they have to start from scratch, like the new kids on the block, it takes more time to learn the requirements for long-term reliability. They are both relatively large enterprises, so they can afford to spend a lot more money and effort to do this. But if you're a small manufacturer, you probably don't need to spend time or money modeling reliability. In today's changing market, it's hard to say, "I have to model this," and put all the money and time into figuring out how reliable it is. You end up copying something from someone else, or saying, "This is what my competitors are using," or, "Let's do a gorilla test. If it passes the test, that's enough." A lot of people steer clear of reliability by saying, "I'm not going to take the time. I'm not going to do a reliability test. I do a durability test, which in my mind is a reliability test." "If it's durable enough to withstand this particular test, then I can use..." That may be true. That may well be the case. However, people have a tendency to protect mistakes. If you're doing durability testing, you may end up spending more money on your supply chain than you actually need to. As a result of over-engineering requirements, your product may become more expensive to test and less competitive in the marketplace.

Johnson: What should smaller manufacturers do to solve this problem? One way is to replace reliability with durability?

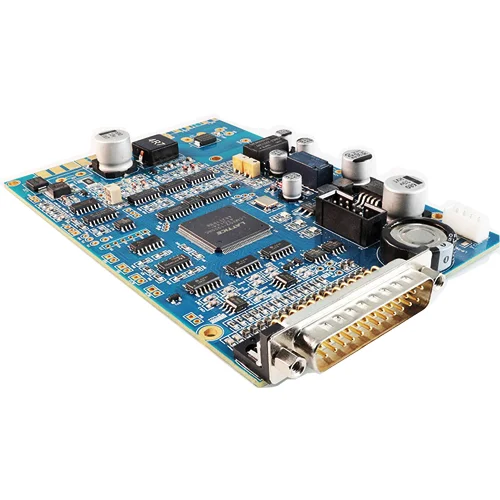

Neves: Durability testing is what most people end up doing. They call these things reliability tests. People mistook this as an ongoing long-term reliability test. But really, what they're doing is a durability test. It's true that they don't understand the connection between the testing they're doing and what's happening with their product in the real world. They set a threshold. Now, at least when it comes to PCBS, people say, "We have to do reflux preconditioning for welds. Why not expand on reflux preconditioning? Expanded from 5 reflux to 10 reflux. If it can survive 10 reflux tests, it will be fine in our environment." Because you have so much extra acceleration, there's a disconnect between what you're doing and what's happening in the field. These extra factors mean little. If you fail the durability test, it doesn't necessarily mean your product is unreliable in a particular environment. It might make sense for reliability, but it might not. There are a lot of products that are being abandoned because they didn't pass the durability test, but they were probably very reliable products in the environment they were intended to be used in. We've long associated ugliness with unreliability. We do a lot of visual inspection, such as evaluating cross sections or looking at solder joints. If it's ugly, we throw it away. We think ugly is unreliable, but it's not. Ugly-looking things can be reliable.

Johnson: We do some nasty testing that doesn't necessarily say anything about the reliability of the product, but it's used all the time. So we also do durability tests, which don't say anything about reliability, but they're used a lot. What other tests are disguised as reliability tests?

Neves: The "nasty" tests are easy to do and relatively inexpensive. That's why these tests are used. It's easy to get an inspector to check for physical defects. It is also easy to run multiple welding thermal cycles to expose problems with the board. If you're going to do 30, 40, 60 or 90 days of long-term testing it's not so easy and it's expensive. The hardest part is really figuring out where your product is going to be used and how much it relates to accelerated testing. That's the hardest thing. It would be a lot easier if people took the time to really understand the problem and really figure it out and work towards real reliability. But not many people take this seriously. The focus is on the performance of the outside of the box, making sure that when the customer wants to open the box, he can open the box.

Mobile phone companies have done a great job of this. My lab doesn't see reliability problems with phone manufacturers because they don't think phones have a life cycle of more than five years. They don't have to keep their products running for too long. Phone manufacturers expect you to get a new phone every year. Because handset manufacturers expect their products to have a very short life cycle in the real world, and they only need to consider that the product is guaranteed for a very short period of time, they don't really need to do reliability testing. They don't spend a lot of money or time on reliability testing. Their only concern is to produce as cheaply as possible.

Johnson: Do you have any other ideas about reliability?

Neves: I'm only talking about reliability in general here, but a lot of people talk about reliability and the conditions for reliability. It's a hot topic. My goal is to encourage people to more carefully distinguish between reliability and durability, to make people realize that they are not the same thing, and not to confuse them. Businesses need to fully understand the test they are using and why they are using it. What's really important is understanding what you're really getting out of the reliability test or the durability test that you're doing. If you're doing durability testing, it's often going to cost you more money because you're setting a higher standard than the reliability of your product in the real world, but it doesn't cost that much to figure out what you want. Taking shortcuts may cost more money or save money. You may be setting the bar too low. If you're using someone else's experience and data, and setting the bar too low, then all the money and time you spend on testing won't guarantee that your product will have an acceptable lifespan in the eyes of your users.

Right now, many companies seem to be more focused on legal liability and doing things that seem hard than understanding what it takes to ensure true product reliability. They looked at the tests and said, you get good reliability by doing more cycles in a high-stress environment. This is not necessarily the case. This confusion has always existed in norms, standards, discussions, and documents. People think of stability tests as reliability tests, when in fact they are durability tests.